Tao Liang: born in 1980, graduate of Academy of Ancient Text, Jilin University,a museologist of the Exhibition Dept. in Henan Museum, dedicating to the study of exhibition of the ancient history.

Lu Zhiping: Graduated from Beijing Union University with a master’s degree in archaeology, holds her position in Liaoning Provincial Museum, with a intermediate academic title of museological researcher, dealing with museological exhibition planning and study on cultural relics.

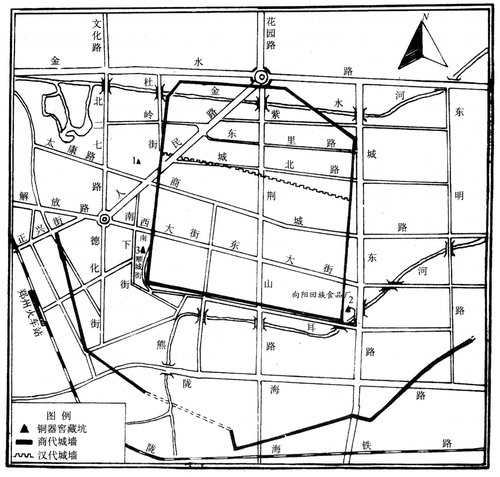

A total of two bronze ding vessels were unearthed from the bronze ware hoard at Zhangzhai South Street. The bottom of the hoard was flattened. The earth surface under Ding Cauldron No. 1 was dug out and lowered to keep the mouth rims of the two vessels at the same level. It seems that such method contains certain ritual meanings. The hoard is located on a high terrace between the Inner City and the Outer City of the Capital of Shang in Zhengzhou. There are two more in the surrounding area of the Capital of Shang: one in Xiangyang Hui Food Factory and the other at Nanshuncheng Street. All these three were built along the outside wall of the Capital of Shang in Zhengzhou (Fig. 2), and 50m away from the city wall. They were probably located outside the moat of the Capital and stood on a high place.

Sacrificial sites dating back to the pre-Qin period mainly include two types: altars and sacrificial pits. According to records in Ji Fa of Book of Rites, kings of the Zhou Dynasty offered sacrifices to their ancestors by three grades. The highest was to establish a temple to offer sacrifices to direct ancestors including the first ancestor Houji, King Wen, King Wu, and great-great-grandfather, great-grandfather, grandfather and father of the then king, collectively known as Seven Temples. Other ancestors would be worshipped on an altar in the ground cleared in the wildness. The last was to clear the ground in the wildness and offer sacrifices on occasions of prayer. Temples were located inside the city, while altars and a cleared area in the suburbs. Though systems of the Zhou Dynasty are recorded in the Book of Rites, traditions of setting up altars and temples for offering sacrifices can date back to the Neolithic Age. For example, the Temple of Goddess (Fig. 3) and the sacrificial altar (Fig. 4) were found at the site of Hongshan Culture in Niuheliang, Chaoyang, Liaoning Province. Such sacrificial sites, dating back to the period from the late Neolithic Age to the early Bronze Age, have been discovered in wide regions of China such as northeast China, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Lixian of Hunan. Most of them are combined with tombs, proving the documents and records about the relationship between sites of temples & altars and sacrifices to ancestors. In the surrounding area of the three hoards of bronze ware in the Capital of Shang in Zhengzhou, there are no tomb sites, seemingly having nothing to do with the cleared areas, altars and temples used to offer sacrifices to ancestors. Among the sacrificial pits in the late Shang or early Zhou Dynasty, those in Beidong of Harqin Left Wing Mongolian Autonomous County and in Hua’erlou of Yixian County, Liaoning Province, are relatively concentrated. They are either located beside famous mountains (eg. in Harqin Left Wing Mongolian Autonomous County of Liaoning Province) or on the bank of a large river (eg. in Ningxiang of Hunan Province). Experts believe that most of these sacrificial pits were dedicated to offering sacrifices to famous mountains and rivers. However, it seems that the hoards in the Capital of Shang in Zhengzhou served different purposes rather than the above-mentioned.

According to Announcement of the Duke of Shao in Book of Documents, “On Ding-si, the third day after, he offered two bulls as victims in the (northern and southern) suburbs.” The reason is that King Cheng of Zhou offered sacrifices to heaven in the suburb. Jiao Te Sheng in Book of Rites also made it clear that the heaven-worshipping ceremony was held in the southern suburb by stating that “The space marked off for it was in the southern suburb - the place most open to the brightness and warmth (of the heavenly influence)”. The place where Zhou people offered sacrifices to heaven was called Circular Mound in the Book of Rites, which refers to an artificial circular high terrace. The three hoards in the Capital of Shang in Zhengzhou are also located on a high terrace, corresponding to the Circular Mound. Therefore, they are probably sites where Shang people used to offer sacrifices to heaven. They are not located in the south suburb of the capital just like what is recorded in the Book of Rites of the Zhou Dynasty, and this is possibly caused by the different systems implemented in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties. In the ancient times, only emperors were allowed to offer sacrifices to heaven, which rulers of vassal states and subordinate states could only provide assistance, hence it was a ceremony to exhibit the emperor’s supreme authority. Moreover, it seems that the large square and circular ding vessels unearthed from the hoards could only be owned by the emperor and used in large sacrificial events of worshipping heaven. In most cases, square ding vessels unearthed from hoards are presented in even numbers with the same designs for a pair. This is related to the tradition that ancestors should be worshipped together with heaven in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties. Strictly speaking, Zhou people regarded heaven as the highest-rank deity, while Shang people regarded emperor as the highest. Be it the sacrifice to heaven or to emperor, these hoards should be used to offer sacrifices to the highest-rank deity by the imperial family of the Shang Dynasty.

Besides Duling Square Ding Cauldron No. 2, there are more vessels of the kind dating back to the early Shang Dynasty:

Duling Square Ding Cauldron No. 1 (Fig. 5) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard at Zhangzhai South Street, 100cm in overall height, 62.5cm in length of mouth, 61cm in width of mouth, 0.4cm in thickness of belly, and about 86.4kg in weight.

Fig. 5

Square Ding Cauldron with Animal-mask Design (Fig. 6) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard in Xiangyang Hui Food Factory of Zhengzhou, 81cm in overall height, 55cm in length of mouth, 53cm in width of mouth, 46cm in length of bottom, 44cm in width of bottom, 0.7cm in thickness of belly, and about 75kg in weight.

Fig. 6

Square Ding Cauldron with Animal-mask Design (Fig. 7) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard in Xiangyang Hui Food Factory of Zhengzhou, 81cm in overall height, 53cm in length and width of mouth, 42cm in length and width of bottom, 0.6~0.8cm in thickness of belly, and about 52kg in weight. Its cross-section is roughly square.

Fig. 7

Square Ding Cauldron with Animal-mask Design (Fig. 8) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard at Nanshuncheng Street of Zhengzhou City, 83cm in overall height, 51.5cm in length of mouth, 51.5cm in width of mouth, 0.5~1cm in thickness of belly, and about 52.9kg in weight.

Fig. 8

Square Ding Cauldron with Animal-mask Design (Fig. 9) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard at Nanshuncheng Street of Zhengzhou City, 72.5cm in overall height, 44.5cm in length of mouth, 43.5cm in width of mouth, and about 26.7kg in weight.

Fig. 9

Square Ding Cauldron with Stud Design (Fig. 10) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard at Nanshuncheng Street of Zhengzhou City, 64cm in overall height, 42.5cm in length of mouth, 42cm in width of mouth, and about 21.4kg in weight.

Fig. 10

Square Ding Cauldron with Stud Design (Fig. 11) unearthed from the bronze ware hoard at Nanshuncheng Street of Zhengzhou City, 59cm in overall height, 38cm in length of mouth, 36cm in width of mouth, and about 20.3kg in weight.

Fig. 11

Square Ding Cauldron with Animal-mask Design (Fig. 12) unearthed from Qianzhuang Site at Pinglu, Shanxi Province, 82cm in overall height, 50cm in length and width of mouth.

Fig. 12

Square Ding Cauldron with Reclining-tiger and Animal-mask Designs (Fig. 13) unearthed from Dayangzhou, Xin’gan, Jiangxi Province, 97cm in overall height, 58cm in length of mouth and 49.3cm in width of mouth.

Fig. 13

Of the early Shang Dynasty, the square ding vessels were generally thinner than those in the late period, and they were seldom found in tombs. Instead, most were unearthed at sacrificial sites. Except for the one unearthed from the tomb in Dayangzhou of Xin’gan, the rest eight of the nine square Ding Cauldron mentioned above were are found in sacrificial pits, revealing that there were possibly strict restrictions on the use of square Ding Cauldron in the early Shang Dynasty.

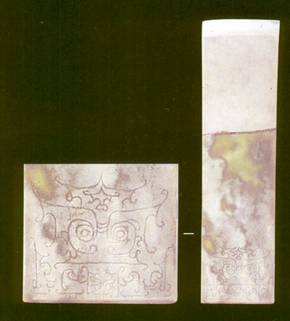

During this period, animal-mask patterns began to be applied on the body of ding, which marks an important step in the development history of bronze ding. In the early Shang Dynasty, such patterns were totally abstract and surrealistic, and might be traced back to the period before the Shang Dynasty, for example, the jade pedant with animal-mask pattern of Hongshan Culture (Fig. 14), the jade cong with animal-mask pattern in Liangzhu Culture (Fig. 15), the jade gui with animal-mask design of Longshan Culture (Fig. 16), the turquoise-inlaid pedant with animal-mask design of the Xia Dynasty (Fig. 17), etc. All these animal-mask patterns served as sacred emblem at the time.

Fig 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Why the unearthed bronze ding vessels, especially the early ones, seldom have a lid?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please feel free to send us email, we are waiting for your answers and participation, and your comments, answers and suggestions will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments some time in the future.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net

Functions and Cultural Significance of Ding

According to records in the Book of Changes · Ding, Explaining Simple and Analyzing Compound Characters by Xu Shen in the Eastern Han Dynasty, Jade Chapters ·Ding Cauldron Section by Gu Yewang in the Southern Dynasties and other books, Ding Cauldron was basically used for cooking. Burn marks have also been found on the bottom and legs of many ding vessels unearthed during archaeological excavation, which proves the above-mentioned function.

What food was cooked in ding? The answer is meat in a general sense. In the ancient Chinese class society, meat was only served to the noble class that was also called “meat-eater” for this reason. In the Western Zhou Dynasty, the hierarchy among the noble class was stricter, and different kinds of meat were allowed for noble people of different ranks. According to historic records, the emperor could use nine kinds of meat at sacrifices and banquets: beef, mutton, pork, fish, dried meat, fresh fish, newly-dried meat, offal and animal skin; feudal lords could not use fresh fish and newly-dried meat; ministers could not use fresh fish, newly-dried meat, beef and offal; scholar-officials could only use pork, fish and dried meat. Inscriptions on some ding vessels also record varieties of meat that were cooked in the vessel. Ding Cauldron was also used to boil water on grand sacrificial occasions. “Peng Kang” Ding Cauldron unearthed from Xiasi of Xichuan, Henan Province, and the Ding Cauldron with coiled serpent design (Fig. 21) unearthed from the tomb of Marquis of Cai in Shouxian County, Anhui Province, are of the kind. However, such ding vessels are mainly found in south China and date back to the period after the Spring and Autumn Period, the earliest one discovered in the Huai River basin.

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

Fig. 21

Ding Cauldron was basically used for cooking but later developed into a ritual vessel. Zuo Zhuan · 3rd year of Duke Xuan records the prevalence of nine Ding Cauldron in the Xia, Shang and Zhou Dynasties when Ding Cauldron became a national treasure and stood for national regime. Many legends of the pre-Qin period about Ding Cauldron casting reflect that the relationship between Ding Cauldron and national regime had been popular throughout the whole stage of early states in China. For example, according to the legend of the Yellow Emperor casting Ding Cauldron before the establishment of early state and the distribution of Zhudingyuan site near Yangping Town of Lingbao City, Henan province, which has been proved to be the place of Jingshan where the Yellow Emperor cast ding, as well as Miaodigou site in its surrounding area (Fig. 22), we can see that the settlement at the time featured a pattern of distributing around a large central settlement and the central settlement began to be separated from common settlements. This reflects the major alliance between tribes then, an important step in the process of the formation of a state. For the birth of an early state, there is a legend of Yu casting nine ding. And legend has it that the ding vessels were sunken into Sishui River when the Zhou Dynasty was overthrown by Qin.

Fig. 22

Duling Square Ding Cauldron No. 2, a bronze ritual vessel in the early Shang Dynasty, is 87cm in overall height, 61cm in side length of the mouth and about 64kg in weight. It was unearthed in the bronze ware hoard at Zhangzhai South Street in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, in September 1974, and is now in the collection of Henan Museum.