Tan Shuqin,worked at museology and archaeology for twenty-five years, mainly devoted to the study of ancient stone carvings, stone reliefs, steles and epitaphs, and ancient Buddhist sculptures.

Li Hui, Museologist from Henan Provincial Antique Exchanging Center, with banchelor's degree, devoted herself to research, collection administration, artifact authentification for more than 20 years.

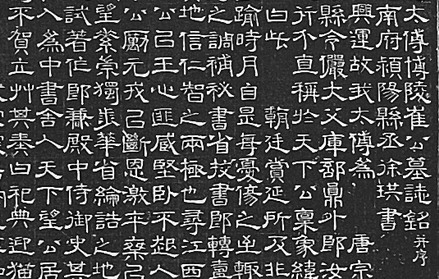

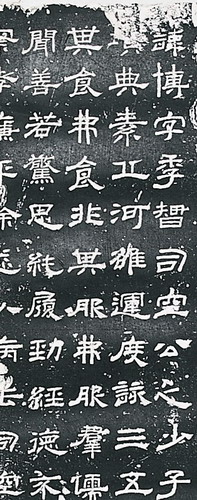

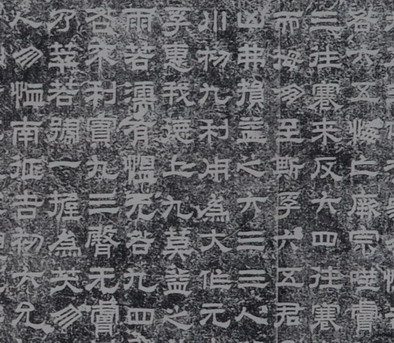

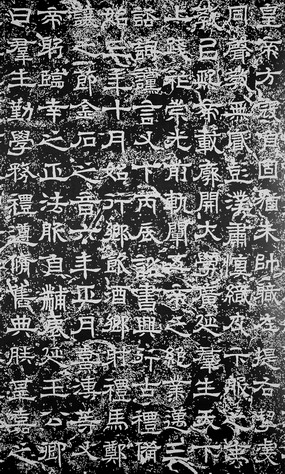

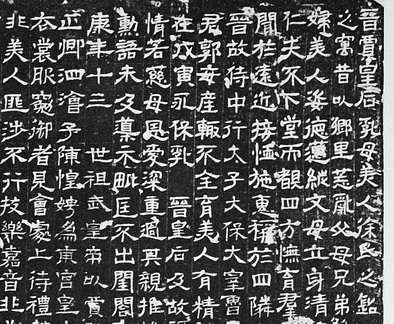

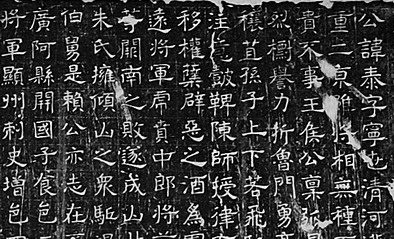

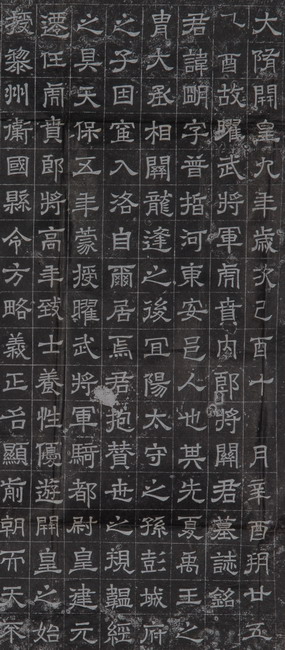

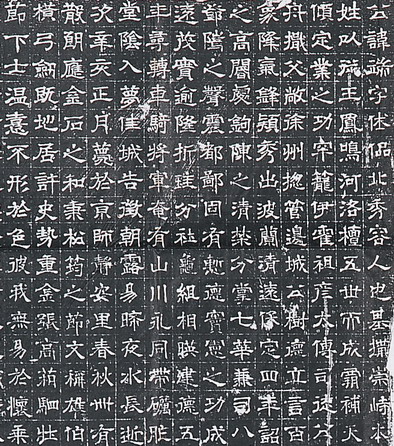

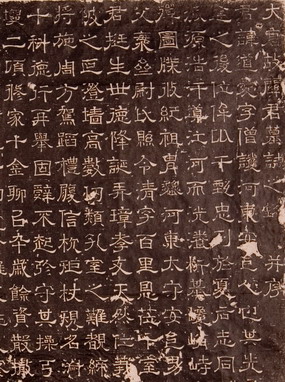

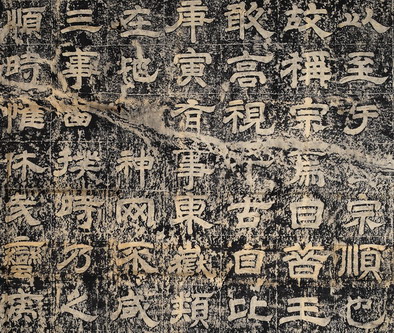

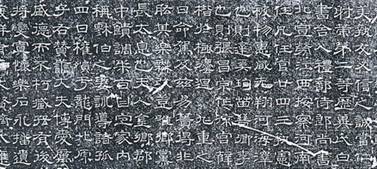

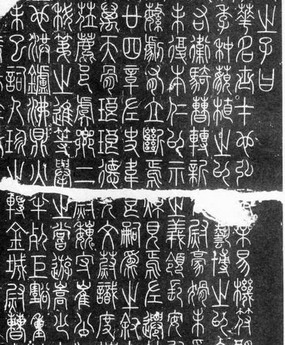

The inscribed tombstone of Cui Youfu is square in shape. Its Luding (flat-topped) cover features an inscription of 12 seal-script characters in three lines, which means “Epitaph presented by the Prime Minister of Tang to Duke Cui, the Grand Mentor” (Fig.1). The epitaph itself, written by Shao Yue and calligraphed by Xu Gong in official script, consists of 38 lines of characters. Each line is made up of 42 characters (Fig.2 and Fig.3). The seal-script inscription on the flat-topped cover is contributed by Li Yangbing.[1]

The epitaph gives an account of Cui Youfu’s life, which covers his direct forebears four generations up his family pedigree, his experience with the imperial examinations, the posts he held, the date of his death, and place of burial. According to the epitaph, Duke Cui, with his name Youfu and courtesy name Yisun, was born to a noble family. In childhood, he was able to study at the Institute for the Veneration of Literature (Chong-wen-guan) thanks to his descent. However, he disdained being granted an official post because of his family. He said, “As this [officialdom] was granted by the court, it is not the right way to make myself known.” He gave up the privilege for enrolling the school. At the age of 25, he became one of the most successful recommended candidates in the imperial examination." During the An Lushan-Shi Siming Rebellion, while the entire nation was in turmoil, Cui led around 100 members of his clan to move south and seek refuge. He volunteered for a post of the Jiangxi command (mu-fu) and was later transferred to the court as Secretariat Drafter (Zhong-shu-she-ren). Then “a cat which suckled rat pups was presented [to His Majesty as an auspicious sign].” All officials congratulated the Emperor but Cui, who believed that a cat which befriended rats could be seen as derelict. He said to the emperor, “Sacrifices were offered and ceremonies held for cats to rid rats. Now this cat suckles rats. Such an act is not unlike administrators compromising with wrongdoers or offenders or commanders not resisting invaders. Heaven forbid this! How can we disobey its will?” The Daizong Emperor accepted his proposal. In 779, the Dezong Emperor succeeded to the throne. Cui Youfu was promoted to be Prime Minister and titles were conferred upon him. He was Grand Master of Splendid Happiness (Guang-lu-da-fu), Vice Director of the Chancellery, and eventually Joint Manager of Affairs with the Secretariat-Chancellery (an official title equivalent to Grand Chancellor in the Tang Dynasty). On the 1st day of the 6th lunar month in the first year of Jianzhong period, he passed away in his mansion in Jinggongli Lane in the imperial capital at the age of 60. A posthumous title, Grand Preceptor, was conferred upon him by imperial edict. On the 24th day of the 11th lunar month in the same year, he was buried ceremonially in his family graveyard in the Mangshan Mountains, Henan.

There are biographies of Cui Youfu in both Book of Tang and New Book of Tang. Cui held official posts through the reigns of the Daizong and Dezong Emperors. During the reign of the Dezong Emperor, he was once Grand Chancellor and reputed for uprightness and incorruptibility. Regrettably, he died after he served as Grand Chancellor for only one year. The inscription on his tombstone contains information concerning his titles and times of death and burial, which are not covered in the two books of Tang. In addition, it also records historical truths about scholars’ moving to the south for refuge amid the social upheaval of the An Lushan-Shi Siming Rebellion.

The writer and calligraphers of the epitaph and tombstone cover inscription were all celebrated artists in the Tang Dynasty (Fig.3). The epitaph, in the form of prose, cites Cui’s life stories and words and combines narrative, emotional expression and argument, thereby vividly depicting a distinguished grand chancellor intolerant of evils, upright, straightforward and able. Li Yangbing, a native of Zhaoxian, Hebei, who calligraphed for the seal-script inscription on the tombstone cover, shared the same grandfather with the father of Li Bai, a great poet of the Tang Dynasty. His highest post was Director of Palace Construction (Jiang-zuo-jian). Xu Gong, who contributed calligraphy to the inscribed tombstone, was a great seal-script calligrapher in his time. Having incorporated features of regular script, his official-script calligraphy is characterized by beautiful, forceful and vigorous strokes. The epitaph, well preserved and legible, is not only of great historic value, but also truthfully representative of the art of seal- and official-script calligraphy.

Epitaphs, as a form of literature, reached their heyday in the Sui and Tang Dynasties. Inscribed tombstones of that period have been unearthed in large numbers, many of which are treasures. The places of discovery included Luoyang--the capital of the Tang Dynasty, Mount Mangshan to its north, Mount Wan’an to its south, Xishan in Longmen, Yanshi, Guanlin and other places. It is estimated that since the end of the Qing Dynasty, as many as 4,000-5,000 inscribed tombstones of the Sui and Tang Dynasties have been unearthed in and around Mount Mangshan alone. Due to the development of the political system in the Tang Dynasty, a great number of officials' tombstones have been preserved. These inscribed tombstones, exquisite in technique and standardised, can reflect the historic changes, evolution of literary style, and features of calligraphy.

Thanks to the work of Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang and Xue Yi in the early Tang Dynasty and Yan Zhenqing in the mid Tang Dynasty, regular script, as a form of calligraphy, was eventually full-fledged in form and rule and established as the official form of calligraphic script. Therefore, the Tang Dynasty has left numerous regular-script tombstone inscriptions. However, regular script is not the only form of calligraphy that can be seen on Tang tombstones. There are also seal, cursive and official scripts. The official script owed its popularity to the Xuanzong Emperor's preference. Because Li Longji, the Xuanzong Emperor, was good at official script, his ministers thus practiced this particular form of calligraphy to please him. This had promoted the resurgence of official script on tombstones, with a refreshing style. In the heyday and middle of the Tang Dynasty, the official script was increasingly adopted for tombstone inscriptions or epitaphs. A lot of famous calligraphers excelled exclusively in official script.

Official script saw an important stage in the evolution of Chinese script in form and calligraphy. It reduces strokes than the smaller seal script, whose curved lines are replaced with straight ones. It is simpler; it switches from circular to square, breaks some joints, and links multiple dots into one stroke. The switch to official script determined the development direction of the Chinese writing system and represented an inevitable shift from complicatedness to simplicity of Chinese characters. In the process of evolution from official to regular script from the Wei and Jin to Southern and Northern Dynasties, the official script had taken on different forms in different historical periods. The varieties of official script, like Han, Wei, Jin and Tang official script, has shown a fascinating diversity on inscribed stones.

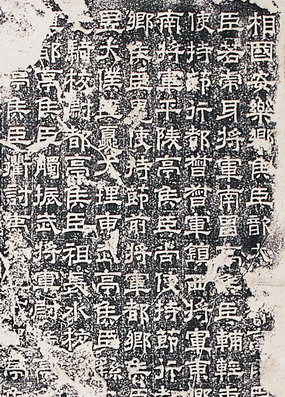

The Eastern Han Dynasty saw official script at its prime. The Gan-ling-xiang-shang-fu-jun-bei Tablet (Fig.4) is a representative work of Han official script. Because Han official script stresses the decorative function of horizontal and right-dropping strokes (heng and na), the curves of horizontal strokes and turns of right-dropping strokes are formed, which have lent elegance to this variety of official script. Cai Yong, the first calligraphy theorist, was active in the Eastern Han Dynasty. Xiping Stone Classics, an inscription he calligraphed in standard Han official script (Fig.5), has been an exemplary work.

Official script had been the officially established script from the Three Kingdoms Period to the Western Jin Dynasty. Most of the tablet inscriptions in the period were in official script. The two famous inscriptions created in the early years of the Cao Wei Kingdom, Shang-zun-hao-zou-bei (Fig.6) and Shou-shan-biao, are very different from works in Han official script in character shape, though it is official script that is adopted. According to a critic, there is an abrupt turn at the beginning of every stroke. This variation of official script is known in later ages as "huang-chu script" or “Wei official script”. It was the product of the first evolution of Han official script, which heralded zhenshu script (lit. “real script”) of the Six Dynasties.

Tablet inscriptions of the Western Jin Dynasty were invariably in official script. A continuation of Wei official script, it has little difference from its predecessor in writing. Regular, elegant and dignified, it features regular structures and brush-using techniques for characters, with a universal style. Such tombstone inscriptions of the Wei Kingdom in the Three Kingdoms Period have all been unearthed in Luoyang and Yanshi, with distinctive features of the time and region. Hence it has been referred to by scholars as "Luoyang Script of the Western Jin Dynasty". Representative works in this variety of official script include the San-lin-pi-yong-bei Tablet (lit. “His Majesty paid three visits to Piyong”) (Fig.7) and epitaph to Xu Yi (Fig.8). Regular and spontaneous, these works show an impressive rhythm.

“Wei tablet” (wei-bei) script of the Northern Wei Dynasty appeared in the transitional stage from official to regular script. However, the years during the late Northern Wei, Eastern Wei, Northern Qi and Sui Dynasties were a brief period of restoration--official script became prevalent again. Inscribed epitaphs, particularly those discovered in Ye, the centre of administration of the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi Dynasties, are almost invariably in official script and of a universal style. A case in point is epitaph to Dou Dai of Northern Qi (Fig.9). Such a phenomenon proves the instability of regular script in transition during the Northern Song Dynasty. Regular script had not taken shape and the rules were yet to be established.

Official script epitaphs account for a large proportion among inscribed epitaphs of the Sui Dynasty. As a continuation of the script restoration in the late Northern Dynasties, this trend had hindered the normal development of regular script [2]. Seal and official-regular scripts at the time showed some features of official script. There were some hybrid works of seal and official scripts in which seal script predominated. They not only discarded the antique techniques but also lacked novelty. The inscribed epitaph to Guan Ming (Fig.10), a work of the Sui Dynasty, is a case in point. The official script shown in this work is regular and neat in layout and structure. However, there are some regular-script characters. The inscribed epitaph to Er Zhuduan (Fig.11) is basically orthodox, with slender strokes and skilful techniques. Though there are some features of regular script, they are not very prominent. As a result, the inscribed epitaph has stood out of Sui official-script works.

Inscribed epitaphs of the early Tang Dynasty that have been unearthed, with features of official script and regular script juxtaposed, have shown the aftermath of the script restoration from the Northern Dynasties to the Sui Dynasty. Cases in point include the inscribed epitaphs to Guan Daoai (Fig.12) and Qu Tutong.

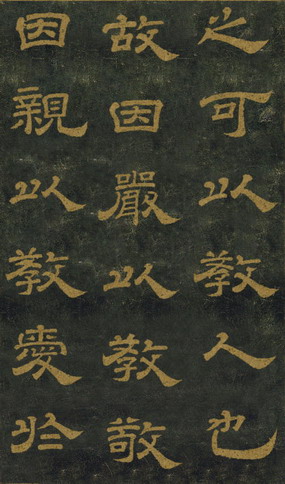

As the Xuanzong Emperor loved ba-fen script (lit. “80% official script”), official script became immensely popular in the heyday of the Tang Dynasty. The Inscription on Mount Taishan (Ji-tai-shan-ming) and The Classic of Filial Piety on Stone Base (Shi-tai-xao-jing), calligraphed by Emperor Xuanzong in official script, are well known among preserved official-script tablet inscriptions. Inscriptions on Mount Taishan was engraved in the 13th year of Kaiyuan period in the Tang Dynasty. When the Emperor Xuanzong held the grand sacrificial ceremony paying tribute to the Heaven and Earth, he had an inscription engraved on the gigantic cliff at the bottom of Daguan Peak (Peak of Great Views). Popularly known as Inscribed Cliff of Tang (Tang-mo-ya), it bears the Xuanzong Emperor’s calligraphy in ba-fen script (Fig.13). The Classic of Filial Piety on Stone Base (Fig.14) combines the Xuanzong Emperor’s official script calligraphy of an annotated version of The Classic of Filial Piety written by Confucius and the Suzong Emperor’s calligraphy on the tablet top. A joint work of Confucius and two emperors, this inscribed tablet is a national treasure at Beilin (“Forest of Inscribed Tablets”) Museum in Xi’an. Now it remains smooth as if newly created. Li Longji (the Xuanzong Emperor) earned the reputation as one of the famed emperor calligraphers in the history of Chinese calligraphy.

Excellent official-script epitaphs of this period have been unearthed in large numbers. The inscribed epitaph to Zhang Tingui (Fig.15), for example, to which Xu Hao contributes calligraphy, is exemplary of official script in the Tang Dynasty. Now the work is in the collection of Henan Museum.

Fig.15 Rubbing of the inscribed epitaph to Zhang Tingui, Tang Dynasty (part)

Though belonging to the category of official script, Tang official script is drastically different from Han official script in style. Han people had derived their variety of official script from seal script. Their style is characterised by an interesting simplicity. Tang official script, however, stemmed from regular script. Compared with its Han predecessor, it lacks the simplicity and vigour distinguishing Han official script, but is neat and regular, with a special charm. Meticulously composed, official-script works of the Tang Dynasty has ridded itself of the features of Han official script except for rounded strokes and pauses, incorporated some features of regular script, and increased the height of characters. These have become defining characteristics of Tang official script.

The tombstone cover of Cui Youfu, to which Li Yangbing contributed his seal-script calligraphy, has been one of the highlights of the inscribed tombstones of the Tang Dynasty. With Li Si, Qin statesman and calligrapher, as his model in calligraphy, Li Yangbing has been reputed as No.1 seal-script calligrapher after Li Si, "the man who invented smaller seal script". Li Yangbing’s calligraphic works in seal script preserved on inscribed stones were mostly re-inscribed in the Song Dynasty. A case in point is Inscriptions of the Three Tombs (San-fen-ji) (Fig.18) of the second year of Dali period (767) in the Tang Dynasty, now collected by Beilin Museum in Xi'an. Adopting the yu-jin (“jade-chopstick”) technique, the work features strokes of the same thickness, curved in an elegant manner. It is Li Yangbing's representative work.

Though there are only 12 characters on the tombstone cover of Cui Youfu, the calligraphic work by Li Yangbing, being well preserved, is very rare because most of his other works, re-inscribed in the Song Dynasty, could not preserve the beauty of his original strokes.

Can you name the Chinese idiom derived from the inscribed epitaph to Cui Youfu?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please feel free to send us email, we are waiting for your answers and participation, and your comments, answers and suggestions will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments some time in the future.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net

Ba-fen Script

Ba-fen script was invented by Wang Cizhong, calligrapher of the Eastern Han Dynasty. It is thus named because 80% of its features are borrowed from Cheng Miao’s official script and 20% from smaller seal script. Viewing from character structure, ba-fen script does not constitute a new script and still falls into the category of official script. However, compared with typical official script, it is in some ways different particularly at beginning and ending strokes. Horizontal strokes of ba-fen script, featuring “a silkworm’s head and a wild goose’s tail”, is far more beautiful than typical official script. Such differences were closely associated with the processing techniques of the writing brush. [3] Because ba-fen was initially a general name for various scripts in transition and it was limited to this specific variety of official script in later times, there have been different theories. One theory stated that it was thus named to be distinguished from regular script in the Tang Dynasty. Tang people had referred to regular script as official script, while classifying Han official script into fen-shu, ba-fen, official-regular script, etc. To distinguish regular script from official script in the Tang Dynasty, the former was referred to by later generations as "contemporary official script". Another theory said that ba-fen script got its name because it showed an inverted V-shaped composition. The latter theory has been very popular in modern times. Therefore, the common names such as ba-fen script (ba-fen-shu), fen script (fen-shu), and fen official script (fen-li) all refer to official script, particularly official script in its mature form.

Notes:

[1] See Zhang Shaoliang, Zhao Chao. A Collection of Tang Epitaphs. Chinese Architecture 004-1822.

[2] Zhang Tongyin. A Calligraphic Study of Sui and Tang Inscribed Epitaphs. The Cultural Relics Press. 2003,8.

[3] Philology. Hong Kong: Gangqing Press.1979:62