Deputy Curator and researcher of Henan Museum;

President of Henan Provincial Institute of Ancient Musical Culture;

Vice-director of Musical Instrument Committee, Museums Association of China;

Vice Secretary General of the Chu Culture Society of China;

Managing Director of Han Painting Society of China;

She has been devoted herself to Research on artifacts, archaeology, museology, and exhibition planning.

About the Jiahu Site

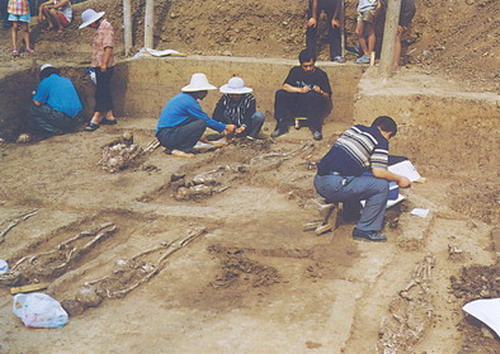

The Jiahu site dating back to the Neolithic Age in Wuyang, Henan Province, was discovered in the early 1960s. During the 10-plus years from May 1983 to June 2001, archaeologists conducted seven excavations of the site, which uncovered an area of 2,657.6 square metres. Fifty-three housing sites, 11 pottery kilns and 445 tombs were cleared; and more than 5,000 cultural relics and fossils including pottery, stone and bone implements were unearthed. Among them there are 30 bone flutes, 17 carved symbols, and thousands of carbonised rice grains. The carbon-14 dating results reveal that the Jiahu site dates back to 9,000-7,800 years ago.

What were these people like? How was this civilisation they created in a transitional region between the Yellow River and the Yangtze?

A large variety of pottery, stone and bone implements were unearthed here. Exquisitely and regularly processed, they show traces of grinding, sawing and drilling, which prove that Jiahu man had mastered the major skills characteristic of the Neolithic Age. There are complete sets of fishing and hunting implements, cooking utensils and water containers.

A large amount of cultivated rice grains and husk imprints unearthed here prove that this place was one of the places of origin of Chinese rice. The material evidence including stone mills, grinding staff and stone spades indicates that artificial cultivation, harvesting and processing had become a mature means of production 8,000 year ago.

Bones of tamed animals including swine, dogs, and a few number of oxen and buffalo have also been discovered. This proves that Jiahu was one of the earliest places where livestock was tamed and raised. Within the premises of the site, traces of horses, sheep, turtles and cranes are also discovered. This shows that Jiahu man, our ancestors, already had a colourful lifestyle.

The examination of the adhesive matter on the pottery unearthed shows that Jiahu man had mastered to the technique of brewing wine 9,000 years ago. The raw materials they used included rice, honey, grapes and hawthorns. So far, the ancient formula has been verified.

The symbols carved on the turtle shells, bone, stone and pottery implements indicate that symbols or characters in its primitive form had been developed during the period of Jiahu Culture 8,000-9,000 years ago. This oldest script in embryonic form provides more important evidence for the origin of characters. The symbols on the pottery and turtle shells bear evidence for the worship of birds and the sun. In this regard, Jiahu man was close to the Taihao clan of the Dongyi Tribes.

The turtle shells with stones inside, the bone flutes, the numerous sceptre-like implements (a token of power and status), Y-shaped bone implements and pottery bearing the motif of the sun prove that primitive religion engaging in reverence, exploration and worship had emerged in their dealing with changeable Nature full of mysteries.

The bone flutes and the stones in the turtle shells show that Jiahu man had already acquired knowledge of integers above 100 and mastered the operational methods of integers. This finding is extremely important to studies on the origin of weights and measures and their relations with music in China.

The over 30 bone flutes unearthed at the Jiahu site are the oldest, best preserved pipe instruments discovered so far. Made from crane ulnae in a standard manner with regular form, they may be classified into two-, five-, six-, seven- and eight-hole flutes of the Early, Middle and Late Stages. As tests conducted by researchers have shown, the seven-hole flutes have a heptatonic scale and can be used to play tunes. These findings have pushed the origin of music in China over 5,000 years back.

Over the past decade, archaeologists led by Mr. Zhang Juzhong, who has presided over the excavation of the Jiahu site, have worked diligently to gradually unveil the mysterious Jiahu site of the Neolithic Age in Wuyang.

In September 2013, archaeologists conducted the eighth excavation of the Jiahu site and unearthed more than 600 items/pieces including clay pottery, stone, bone, horn and ivory implements. Three bone flutes, namely, a two-hole one, a five-hole one and a seven-hole one, were among them.

A long time ago, in this humid, rainy region with distinctive four seasons, where there were sparse forests, luxuriant grass, lakes and marshes, fish, birds and beasts flocked and multiplied. In a human settlement, semi-underground caves, ground and tilted houses, which all faced the centre, were scattered and surrounded by ditches and canals. People fished, hunted, grew rice, built houses, raised livestock, made pottery, grinded stones, processed bones, and brewed wine......The brisk, melodious music of the bone flute lingered in the cooking smoke and above the lakes.

On what occasions did Jiahu man play the bone flute 9,000 years ago?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please feel free to send us email, we are waiting for your answers and participation, and your comments, answers and suggestions will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments some time in the future.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net

People have always associated the origin of music in China with the Three Wise Kings and Five August Emperors’ creation activities 5,000 years ago. The unearthing of the Jiahu bone flutes dating back to over 8,000 years ago pushed the origin of Chinese music thousands of years back. As far back as 8,700 years ago, our ancestors had been able to produce sounds of a quasi-heptatonic scale with the bone flute. The discovery of these material objects in archaeological investigation has illustrated the primitive living form of music in China in remote antiquity.

Of the nearly 30 bone flutes unearthed since 1983, nearly 1/3 are preserved fairly intact, seven of them have passed tone test. In the following decade, many archaeologists have carried out studies on the Jiahu bone flutes via tone test and tentatively revealed their musical effect and acoustic features.

First of all, researchers have studied how the bone flute, as one of the oldest, well-preserved wind instruments, was played. They have proposed an oblique-blowing theory and held that such a method ensures better friction and concussion of airflow and tube walls and produces a rich, profound sound. However, the results of the actual tone tests in the archaeological report on the Jiahu site in Wuyang have mostly been based upon the vertical-blowing method; and the bone flute music posted on the website of British magazine Nature has also been recorded via the method.

From ancient China to today’s Kazakhstan and Xinjiang, China, there have always existed musical instruments in primitive forms which are played with the oblique-blowing method, such as the eagle bone whistle. Another special instrument worth mentioning is the chou, which is still played in Taoist music in the Central Plains region. It is very similar to the bone flute in shape and design. The ancient technique of oblique blowing can enable the flute with two open ends to produce solid, musical sounds.

Secondly, researchers have measured the acoustic features of the bone flutes discovered in the archaeological excavation at the Jiahu site. In 1989, after Mr. Huang Xiangpeng conducted an acoustic test of the well-preserved M282:20 bone tube, he concluded that the instrument has a hexatonic scale at least, or likely a full-fledged ancient heptatonic xiazhi scale.

In the earliest stage of music, people’s understanding of scale and pitch was limited. However, we cannot underestimate prehistoric man's perception of music sounds and creativity. The natural environment where they lived had more harmonious sounds from Nature. There are many factors influencing the pitch and mode of music sounds produced by the bone flutes. The results published by Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology in the archaeological report on the Jiahu site in Wuyang show that people’s appreciation of musical sounds and scale has undergone a cumulative process.

Music has been present throughout the evolution of human civilisation. The mystery how music originated is bound to be unveiled as the mystery of the origin of human civilisation is resolved.

One of the fundamental needs of life in Nature is to make their own sounds in the course of growth and death. Such sounds concern their love and reverence for Nature, memories of the bygone past, the worship of deities, and the understanding of life and death, love and hatred. All this is expounded in the truest, most beautiful sound that can be conceived in the human mind. That sound is music.

From where the Jiahu bone flutes were unearthed and how they had been preserved and used, it can be seen that the dead were, in most cases, interred with large quantities of burial objects, which borne evidence for their special status in the entire settlement. The bone flute was not merely a musical instrument used to summon otherworldly beings or in hunting, but also a vehicle through which ancient Chinese believed that they could achieve communion with immortals and convey the wishes and prayers of the entire clan.

In Tomb No. 344 at the Jiahu site, besides the two bone flutes by the left arm, there were also eight sets of turtle shells filled with stones in the place of the skull. In the tombs where bone flutes were discovered, there tended to be turtle shells filled stones and Y-shaped bone implements. There must be some special associations between those items. A passage in Jian-ai (‘Universal Love’), Mo Tsu mentions a legend set in the reign of Tang, founding monarch of the Shang Dynasty, which says, ‘After the fall of Jie [the last monarch of the Xia Dynasty], there was a severe famine lasting seven years. Tang offered himself as sacrifice. With nails and hair cut, clad in a cloth gown and wearing cogon grass, he prayed in a mulberry forest. Then a heavy rain came.’ When a clan met with some major mishap, the people in the above-mentioned tombs were likely to be sacrificed or volunteer as sacrifices. A lot of historic materials have indicated that in the primitive society music was closely associated with deity- and human-entertaining activities related to religion and sacrifice. The scale and tones of music originated from ancient people’s perception of the unknown part of Nature and expression of their different emotions, as well as from their attempt to communicate with other beings and deities.

The Jiahu bone flutes were made from ulnae of large cranes. In remote antiquity, Jiahu was a place with numerous rivers and lakes. The wetland environment made it an ideal habitat for large-sized birds. The crane, a large wading bird, often lives in wetlands. So far, there exist 15 crane species in the world, of which 9 can be found in China. The red-crowned crane is the most famous species in China. Historically, it was widely distributed in central and eastern China and loved by ancient Chinese in the Central Plains region. A poem line in ‘He Ming’, Lesser Court Hymns, The Classic of Poetry, writes, ‘The crane cries in the ninth pool of the marsh,/ And her voice is heard in the [distant] wilds.’ The windpipe of the crane is as long as over 1 metre, five and six times the length of a human being's. It coils at one end between the breastbones. When a crane stretches its neck and whoops, strong concussion can be generated so that the sound may be transmitted for thousands of metres. On the basis of this observation, ancient Chinese developed a theory long ago that ‘a flute made from a crane bone gives out clear and melodious sound.’

Strong and hollow inside, red-crowned crane bones are seven times harder than human being’s. Such features are conducive to the generation of air concussion and musical sounds. When a flute was made, first of all, the joints at the two ends of a bone were sawn off. Then the positions of the holes evenly distributed on the trimmed hollow bone were marked before they were bored. Therefore, on a well-preserved bone flute, we can see marks carved when the holes were spaced. Arrayed in a straight line, the holes are round and slightly taper from top to bottom. Some of the bone flutes have shown slight traces of petrifaction, which sheds light on the fact that they have a long history of nearly 10,000 years.

In recent years, the discovery of bone whistles and flutes has also been reported from time to time in foreign countries. Archaeologists have discovered several really old bone flutes worldwide—the oldest to date. For instance, a two-hole bone flute was discovered in Slovenia, which was made by the Neanderthal man from a cave bear shank 50,000 years ago; a three-hole bone flute made 35,000 years ago from a crane leg bone was discovered in a mountain cave to the southeast of Blaubeuren, a city in southern Germany.

China's archaeological investigation into Neolithic sites in recent years has also led to the discovery of similar bone flutes at some sites. A five-hole flute made from an avian bone 8,000 years ago was discovered at the Xinglongwa site in Aohan Banner, Inner Mongolia. In 1973, at the Hemudu site (dating back to about 7,000 years ago) in Yuyao City, Zhejiang Province, several two-hole bone whistles were unearthed. The ten-hole bone flute discovered at Zhongshanzhai, Ruzhou City, Henan Province, has been identified as a pitch-carrying instrument used 7,000 years ago.

All those above-mentioned instruments differ from the Jiahu bone flutes in that the latter, discovered in large numbers alongside abundant other relics, have shown a distinct line of evolution, as well as marks of standardised processing, long-term use and safe-keeping. More importantly, as the oldest, well-preserved pipe instrument, they have relatively diverse variations in pitch, timbre, scale and mode. Of all the things around them, the early people at Jiahu picked the bone of the somewhat mystical red-crowned crane as the material for the musical instrument. In so doing, they managed to find a vehicle and embodiment that conveys the meaning of life through 8,000 years.

This is a flute made 8,700 years ago and unearthed at the Neolithic site at Jiahu, Wuyang, in the upper reaches of the Huaihe River in central Henan. Made from a hollowed bird ulna, the instrument can produce sounds of heptatonic scale. It is the oldest, best preserved wind instrument ever discovered in China. The unearthing of this remarkable artifact, which has updated our understanding of the origin of music in China, was a memorable event in the Chinese history of music.

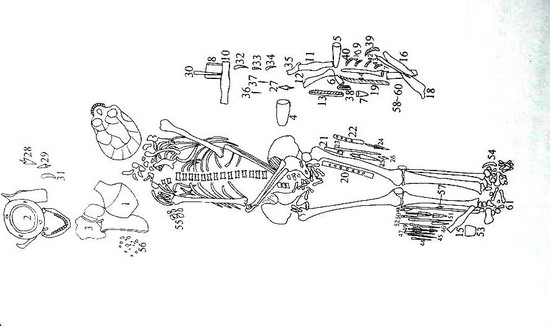

A total of near 30 bone flutes were unearthed at the Jiahu Site. Apart from an unfinished one discovered in a pit and two damaged ones found in a stratum, the rest 23 were unearthed in 16 tombs. Of the tombs, seven tombs each had 2 bone flutes interred, and the other nine each had one interred. The tombs with one or two bone flutes accounted for 4% of the 445 tombs that have been excavated at the Jiahu Site. In these tombs, whose dates span more than 1,000 years and which concentrate in one zone, the bone flute or flutes were, more often than not, discovered alongside implements of sorcery or divination, such as turtle shells and ‘Y-shaped implements’. Therefore, the owners of the bone flutes may have been sorcerers, priests, and chieftains and thus occupied a special status in the Jiahu clan.

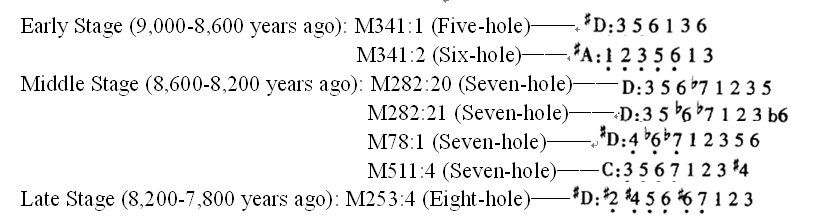

Twenty-two bone flutes were unearthed form 15 tombs of the Jiahu site. By abundance of burial objects, they may be classified as belonging to three stages—the Early Stage (approximately 9,000-86,00 years ago): the flutes have 5 or 6 holes and may produce sounds of four or five tones; the Middle Stage (approximately 8,600-8,200 years ago): the flutes have seven holes and may produce sounds of six or seven tones; and the Late Stage (approximately 8,200-7,800 years ago): the flutes have seven or eight holes and may produce sounds of seven tones as well as of altered tones.

Except in M341 and M344, where the flute bones were placed by the limb bones of the dead, the others were mostly placed by the two sides of the dead’s thigh and shin bones. The two best preserved and exquisitely made flute bones were unearthed in M282 of the Jiahu Site, where a total of 61 burial objects were discovered. With a total length of 22-23 centimetres, they look light brown all over. The bone flute numbered 282:20 has an extra small round hole between the 6th and 7th holes. Scholars have different opinions on it. Some think that it is inherent in the bone; and others hold that it is a tuning hole drilled to adjust the sound produced from the seventh hole. A close study of this well-preserved flute by musicians Tong Zhongliang, Huang Xiangpeng, Xiao Xinghua, et al., has revealed that it has a scale and can produce rhythmical, musical sounds of accurate tones. Archaeological investigation has turned out that the 282:21 flute had once been broken and repaired when the tomb owner was alive. Fourteen small holes had been drilled in the wall of the broken place, and then a thin cord was used to tie the broken parts together with care. The middle part of the flute shows traces of textile wrapping, which may have been used to protect it from damage. The fact that it had been so cherished is enough to prove the value of the bone flute in that period.