The New Culture Movement and the May 4th Movement had inflicted unprecedented impact on the traditional art of China, consequently, the Chinese painting started to take on a new form. In artistic creation, there had gradually emerged painters in groups, who based themselves in metropolitan cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, and many of the traditional artists began to change their ways with distinctive painting styles. Among them, the most successful personalities included Xu Beihong, Qi Baishi, Wu Changshuo, and Liu Haisu, etc., whose spirit of innovation, other than anything else, helped to establish their iconic status in the art circles.

In terms of artistic philosophy, Xu Beihong expressed disdain for the style of “Four Wangs”, preferred the tradition of Song dynasty, oppose the simple restoration of ancient ways, and advocate his own realism opinion in painting by exploring the nature, sticking to the objective portrayal.For Qi Baishi, however, the best art lied in the subtle balancing between likeness and unlikeness, which he regarded as the ultimate goal one could pursue in the artistic realm. Determined to explore new styles in his late years, Qi Baishi tried to learn from those painting masters such as Xu Wei, Zhu Ta, Shi Tao and Wu Changshuo, among whom he particularly admired Xu, Zhu and Wu who were big three of traditional Chinese painting during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. A poem he composed goes like this, ‘Both Qing Teng and Xue Ge were no ordinary souls/And Laofou performed even better in his late years/I’d rather become a walking dog (attendant) in the underworld/To be in service to thou in turn.’ Qing Teng, as mentioned in the poem, refers to Xu Wei, aka Xu Wenchang, the Ming Dynasty master who created the genre of the freehand brushwork flowers and birds painting in the history. Xuege, is Zhu Ta, widely known as Badashanren. And Laofou, namely, Wu Changshuo, who was among the most influential Shanghai school painters of the late Qing Dynasty. By showing his desire to become a ‘walking dog’(attendant) of those three outstanding persons, Qi Baishi clearly confirmed how much he adored them. Qi Baishi readily learnt from others, and eventually developed his own style of red flowers and ink leaves painting, whereby he displayed his prowess in depicting not only plants (melons, fruits, vegetables, flowers, etc.) and animals (birds, insects, fish, etc.), but also figures and landscapes in a wild freehand brushwork, which brought him the honorable title ‘Wu of the South and Qi of the North’ jointly shared with Wu Changshuo. In 1956, Chinese traditional painter Wang Xuetao invited Piccaso to visit China, to his surprise Piccaso said, ‘I dare not to go, because over there they have a great Qi Baishi! Mr. Qi’s ink and wash fish was not colorized, yet it enabled us to visualize the long river and the swimming fish in it; not to mention the ink bamboo and orchid which are way beyond me.’ One can come to realize the value of Qi Baishi through such remarks made on him by a distinguished western painter.

Both being distinguished personalities in the history of modern art, Wu Changshuo and Qi Baishi are known widely as ‘Wu of the South and Qi of the North’, and enjoyed the honor of masters of four arts (poetry, calligraphy, painting and seal cutting).

Wu Changshuo (1844-1927), originally named Jun, followed by Junqing; also styled as Changshuo, Cangshi, Foulu, Kutie, etc. He was a native of Anji, Zhejiang and is recognized as an accomplished master of art.

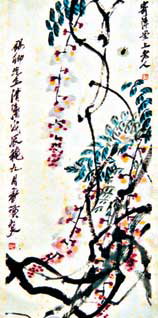

The Hanging Scroll Wisteria by Wu Changshuo of the Qing Dynasty, presently collected at the National Palace Museum, Taipei,is a work of ink and color on gold-dusted paper, measuring 163.4cm in length and 47.3cm in width. The last one of the four flower-themed hanging scrolls, it bears an inscribed poem which reads, ‘The drooping wisteria is bearing clusters of purple flowers/The good spring days seem to stay on the vines/May the abundance of flowers bloom year after year/To fill up the vacancy of my studio.’ Affixed to it are, ‘Painted by Wu Junqing of Anji on August 8, the year of Yisi (1905) in the imitation of Shisanfeng Cottage’s Works’ and the ‘Seal of Wujun’.

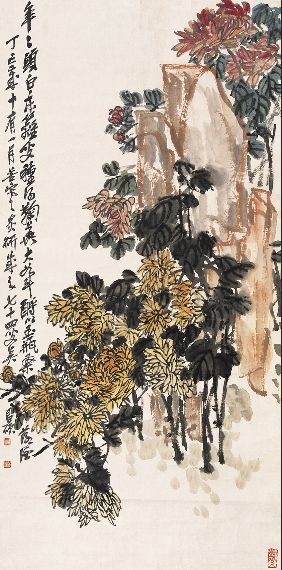

The Chrysanthemum and Rock is a masterpiece of wild freehand brushwork done by Wu Changshuo in his late years. The poem affixed thereto reads, ‘Year after year the hoary old man tills the soil by the country fence/Planting chrysanthemums that grow as big as bucket/In whose company I enjoy Sangluo wine contained in jade bottle. Done in November, the year of Dingsi (1917) despite the bitter cold, by the 74-year-old man Wu Changshuo.’

The Wisteria, currently kept in the Shanxi Museum, is a hanging scroll of ink and color on paper, measuring 98cm longitudinally and 40cm horizontally. On the upper right corner are an inscription ‘Old Man of Lotus Hall’ and a raised seal ‘Woodman’. The inscription on the left side reads, ‘Done by Qi Huang in September, the year of Wuchen and presented to esteemed Qingguo’, which is accompanied with a seal ‘Old Man Baishi’. The year of Wuchen is 1928 when Qi Baishi was 65. Which is to say, the work was accomplished during the medium stage of his career.

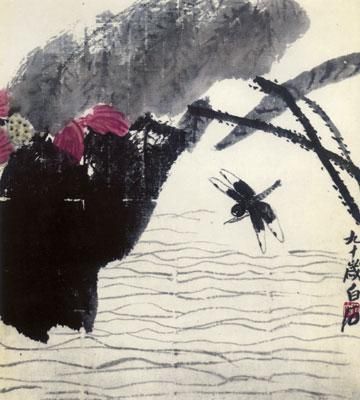

The Lotus and Dragonfly, by Qi Baishi, collected at the Shanghai Museum, ink and color on paper, height 39cm, width 35cm. A work of two lotus leaves on the upper left plus a dragonfly, inscribed ’90-year-old Baishi’.

While attaching importance to innovation, Wu Changshuo and Qi Baishi both did not oppose imitation, in fact, they were quick to learn the merits, by meticulously imitating their works, of those masters such as Qingteng, Xuege, Qingxiang, Shitian and Bai Yangzhu for whom they held high esteem. The area where Wu Changshuo performed best was flowers of freehand brushwork, in which he favored the use of contrastive colors, especially carmine, so as to arrive at an effect featuring rich and bright colors. He once said, ‘What makes me strong is that, I can paint well the way I work with my calligraphy.’ A splendid scene, combined with a beautiful poem written in elegantly free style calligraphy, plus a simple, artistic seal, making up an artwork that integrates poetry, calligraphy, painting and seal cutting -- this way of painting flowers and birds is the legacy that Wu Changshuo left to modern times with significant influence.

On the other hand, Qi Baishi was an expert of monocolor works which were marked by freehand brushwork. His works are typical of simple and unvarnished subjects depicted in intense, vibrant tone, free of vulgarly superficiality and fancy decoration. Of all the painters, ancient and modern, he was the one who was the most unconstrained in using colors, most versatile in painting techniques, and adeptest at changing. Pan Tianshou said, ‘Elderly Baishi of modern times is a follower of Changshuo on layout and colorization, but with changes. Superficially, he is different from Changshuo; in essence, however, his skills are developed from Changshuo, which is evident to a person with sense.’ Quite interestingly, Hu Peiheng, a friend of Qi Baishi said, ‘From the perspective of artistic quality, elderly Baishi is quite above Wu Changshuo in terms of range of subject, novelty of composition, richness of colorization, etc., and is doing equally well as Wu Changshuo in terms of the mastery of harmonious and implicit ink strokes, each with personal characteristics, though. If we take into account of both thoughtfulness and artistic value, elderly Baishi for sure way surpasses Wu Changshuo.’ Zhang Daqian commented, ‘Between Wu Changshuo and Qi Baishi, if I were to make a comparison and tell who is better, my choice is on Qi’. Clear enough, Qi Baishi is another example of pupil outdoing his master.

1) As a great master of art, Qi Baishi used so many different names in his lifetime. But why did he have such an affection for ‘Baishi’?

2) Perusing at the shrimp paintings by elderly Qi Baishi, one can see that the shrimps are usually depicted with their head turning to the left side, none to the right side. Why so?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please feel free to send us email, we are waiting for your answers and participation, and your comments, answers and suggestions will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments some time in the future.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net

Born in Guzhen Village, Hejin City, Shanxi in 1899, Dong Qiwu grew up under the influence of the traditional culture. At the age of 19, he went into the army and joined the Northern Expedition. He preserved the anti-Japanese stance and engaged in the war in Shanxi and Southern Inner Mongolia to protect the country against the invasion. In September 1949, he led an uprising of military and administrative personnel in the capacity of lieutenant general conferred by the KMT Republic. In praise of Dong Qiwu’s great achievements, Mao Zedong said, ‘There’s no one more deserves the rank of general than Dong Qiwu!’ It was Mao Zedong himself who conferred the First Class Liberation Medal to Dong Qiwu in the Hall of Cherishing Benevolence.

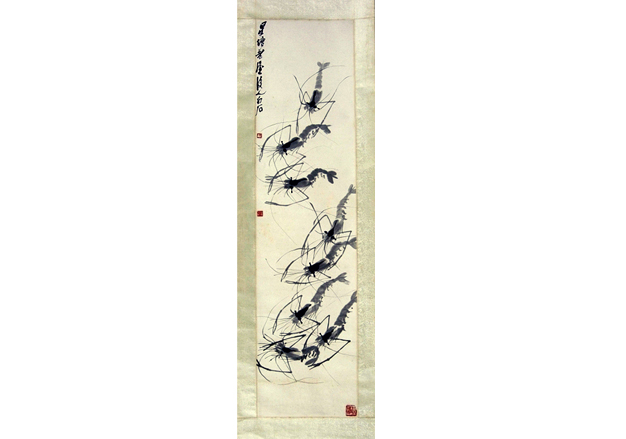

The Six Shrimps was a work Qi Baishi presented to General Dong Qiwu, the anti-Japanese hero. Painted in 1948, it measures 102.8cm in length and 34cm in width, and is full of sublimity. When he was working on it, Qi Baishi was 88 and was at the peak of his artistic career. The six shrimps, typical of Bashi style, come alive on the paper, fresh and vibrant, glowing with eternal artistic beauty. The sturdily-built shrimps and the auspicious number of six were meticulously chosen by Qi Baishi, with which he meant to inspire Dong Qiwu with confidence and valor and wish him good luck and success. For the veteran artist, The Six Shrimps was indeed an expression of his heartfelt yearnings for the early ending of the Anti-Japanese invasion war and the restoration of peaceful life among the common people. At one time, the cross-age friendship between Dong Qiwu and the world famous artist Qi Baishi had become a story that spread afar.

Qi Baishi, a native of Xiangtan, Hunan, born in 1864 and died in 1957 at the age of 93. He was originally called Chunzhi, alias Weiqing, and later renamed as Huang, with pseudonym Baishi and nickname Owner of Jieshanyin House, etc. Awarded the honorable title of the ‘People’s Artist’ by the Ministry of Culture of the Central Government in 1953.

Among Qi Baishi’s shrimp-themed paintings, few had ever come out with as many as eight shrimps in one single piece of work. Yet, this work is an exception, with up to eight shrimps, each vividly portrayed. By applying ink of different shades, the artist created a real live picture of eight shrimps, each with different physical grace, sporting playfully in water. The S-shape composition was aptly used to display a lively scene of the shrimps cavorting around and chasing each other in water. The painter combined different brushwork and ink techniques, thus producing a lifelike, dynamic picture of shrimps swimming in an unrestrained, easy-going fashion. On the upper left corner the author inscribed, ‘Baishi the Descendant of the Old Xingtang House’, below which are two seals, namely, ‘Woodman’ cut in relief and ‘At My Age of 87’ cut in intaglio. On the lower right corner is a corner seal, reading ‘To Become a Rich Man with Three Hundred Stone Seals’.

Qi Baishi was a diligent painter, who devoted himself to artistic creation throughout his career. He was well known in painting shrimps. He had an inborn affection for shrimp which explains why each and every shrimp under his painting brush appears true to life, their bodies clear as crystal and full of unlimited vitality. With the aim of painting shrimps well, he once said, ‘(I will) portray for all insects, express the nature of all birds, and draw my image with my own features;’ and ‘my shrimps look different from those commonly seen. What I have been seeking is spiritual likeness rather than physical likeness, that’s why they are alive.’

Elderly Baishi’s career as a shrimp master may be divided into the early stage (imitating tradition period), medium stage (painting from life period) and late stage (mature period). Talking about the course of his shrimp painting, Qi Baishi said, ‘I’ve changed my shrimp painting styles several times. At the beginning, I sought for rough likeness; then I turned to realism before I opted to stick to the use of shading technique in painting, whose essence I did not grasp until after decades of years of practice’. The Eight Shrimps, as collected at the Henan Museum, is a work completed by him at the age of 87, during his mature period, of course, which can be regarded as a master work of his, and is a precious physical material for our study of Qi Baishi’s paintings.

The Eight Shrimps, a work of art by Qi Baishi, hanging scroll, painted on paper,measured 135cm x 34cm. Purchased in Beijing 1958 and currently preserved in the Henan Museum.

Museologist of the Collections Administration Department of Henan Museum,devoted herself to the protection and research of the collections of calligraphy and paintings.