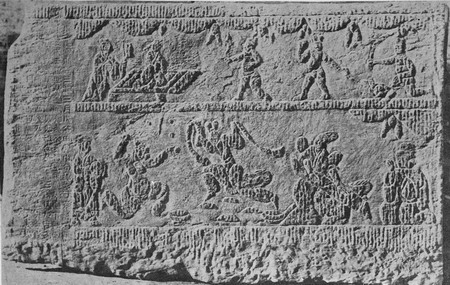

Henan Museum houses a special epitaph for a woman, which was engraved on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month in the thirteenth year of Dali period (778) during the Tang Dynasty. It was unearthed in Luoyang in 1929 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Made of bluestone, it measures 91 cm long, 91 cm wide, and 19 cm thick. The lid, topped with a luding roof (a four-sloped roof with a flat central portion), bears a nine-character inscription in seal script, meaning the Tomb of Wang, Wife of Duke of Anping of Tang, and it is surrounded by floral patterns. The text of the epitaph is written in official script in 48 lines (the last 24 are inscribed on the reverse side), with 29 characters in each line.

The Epitaph of Cui Youfu, Grandson of Wang Yuan: a Well-preserved Epitaph of a Tang Prime Minister This epitaph, which is kept in Henan Museum, was engraved in 780, or the first year of Jianzhong period during the Tang Dynasty. Also unearthed in Luoyang, it measures 107 in height and width, and 21 cm in thickness. It is the only well-preserved epitaph of a Tang prime minister in the collection of this museum (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). The tombstone is square and has a luding roof (a four-sloped roof with a flat central portion). At the top are twelve characters in three lines--'Epitaph of Cui, Tang Prime Minister and Posthumous Imperial Tutor', which are surrounded by incised grass-and-flower patterns. The text of the epitaph is written in official script in 38 lines, with 42 characters in each line. It was composed by Shao Shuo and calligraphed by Xu Gong. The characters on the lid were engraved by Li Yangbing in seal script.

Cui Youfu, whose biography appears in both Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang, served in the reigns of Emperor Daizong and Emperor Dezong. In the reign of Emperor Dezong, he was appointed prime minister and helped to build a clean and honest government. Unfortunately, he died only a year later. The epitaph supplements the historical records in the two books of Tang with the years in which he was given a noble title, died and was buried. According to the epitaph, he died at the age of sixty on the first day of the sixth lunar month in the first year of Jianzhong period at Jinggong House in the capital. He was given the posthumous title of Grand Tutor. His nephew was made his heir and named Zhi. On the twenty-fourth day of the eleventh lunar month of the same year, the government buried him with proper rituals by imperial order in the cemetery of his ancestors on Mangshan Mountain in Henan. His wife was a woman named Wang from Taiyuan, and they he had a daughter. His nephew was made his heir because he had no son.

Both the author, calligrapher and engraver of the epitaph were famous during the Tang Dynasty. The engraver Li Yangbing, born in Zhao County in Hebei, was fond of history and good at writing. In particular, his seal script was so wonderful that he was acclaimed as the greatest master of the style since Li Si, the creator of small seal script. Xu Gong, the calligrapher of the epitaph, was a master of official script. Vigorous and graceful, his seal script is characterized by the incorporation of regular script techniques and elegant downward strokes.

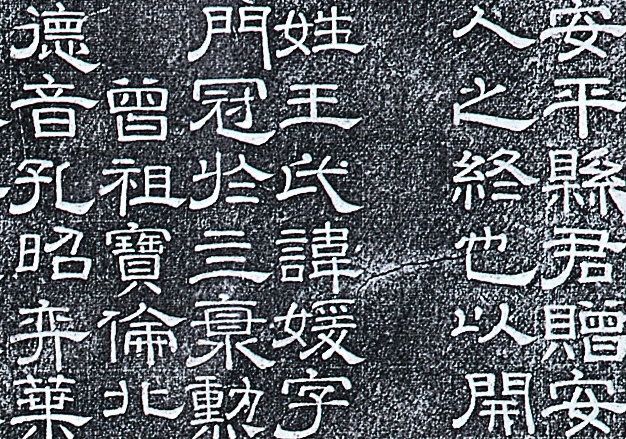

All these epitaphs were written by famous Tang calligraphers in official script (see the rubbing of Wang Yuan's epitaph). As we know, official script appeared in the Han Dynasty, flourished during the Eastern Han Dynasty, while regular script reached its peak during the Tang Dynasty. Why were all these epitaphs written in official script? And can you see any difference between Tang official script and Han official script?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please fell free to send us email, we are waiting for your answer and participation, and your comments or answers will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments in the proper time.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net

Many epitaphs have been unearthed across China, and those about women take up about a third of the total number. The social hierarchy of ancient China put men above women and decreed that men should be breadwinners and women should be housewives. Thus women rarely had the opportunity to take part in social activities or outdoor work. There are few biographies about women in standard or authorized histories, and these are very short. For instance, the biography of Princess Pingyang of the Tang Dynasty only contains about a hundred characters despite her distinguished service to her country. The secondary role of women and their dependence on men are also reflected by the fact that the beginning of most epitaphs about women highlights the official posts or status of their husbands. The women described in epitaphs were from various classes, ranging from consorts of the emperor and women in the imperial family or families of high-ranking officials or ministers to women of humble birth, including commoners, palace maids, and even prostitutes. Such epitaphs, which present a kaleidoscopic historical picture, can help us to understand how women lived in ancient China.

If the value of a man lies in carrying on the tradition and property of the family and success in his official career, that of a woman mainly lies in the practice of the family ethical code. The value of the tomb occupant in women's epitaphs is usually acknowledged in terms of the Confucian requirements of the 'three obediences' and 'four virtues', emphasizing 'morality, modest manner, proper speech, and diligent work'. Most of them were chaste, obedient, gentle, upright and devoted to their parents, with a deep understanding of the way of housekeeping and homemaking. Well educated in the classics and rules of propriety, they respected the elderly and protected the young, treated their parents-in-law kindly, assisted their husbands, and educated their children, behaving with forbearance, modesty and gentleness, so as to maintain harmony among all members of the family. For example, the 'Epitaph of Lu, Wife of Cui' of the late Tang Dynasty describes how Lu brought up the son of her late husband's ex- wife. Women like her were paragons of 'womanly virtues'.

The epitaphs also tell us about the childbirth, health and cultural accomplishments of ancient women. Almost all these epitaphs describe their religious beliefs. Most of them believed in Buddhism. Some gained spiritual comfort by chanting scriptures, some sought peace of mind by burning incense and worshipping Buddha, and some eventually renounced the world and became nuns.

A large number of women's epitaphs have been unearthed, and they involve many historical materials. Some of them are true records of women's whole lives. Epitaphs of women of various classes are highly valuable for the study of women’s life, the treatment of officials' families and women's literature in ancient China. Due to the lack of space, this article only mentions epitaphs that are representative of various classes of imperial China to draw your attention to this subject and offer precious historical data for reference of researchers interested in ancient women’s life.

Wang Yuan's epitaph

This epitaph is special in that the text is quite long (nearly 1,400 characters), so much so that it extends to the reverse side of the tombstone. This represents a bold innovation made during the Tang Dynasty, which broke through the previous convention for engraving tombstones. The text offers detailed information about the life of the tomb occupant Wang Yuan. It not only describes her ancestry, genealogy, marriage and family, but also recounts how she educated her children and kept house by quoting her words in plain language. Generally speaking, few of the primary wives of officials appear in standard or authorized histories. Thus the Epitaph of Wang Yuan offers a true record of the lifestyle of officials' primary wives during the Tang Dynasty as well as the life of aristocratic women during the mid Tang Dynasty.

According to the epitaph, Wang Yuan, Zhengyi by courtesy name, was born into a family of officials in Jinyang, Taiyuan. At the age of thirteen, she married Duke of Anping Cui Kai. Since then, she had conducted herself with modesty and gentleness and done her duties without complaint, helping her husband to maintain unity in the family. After her husband's death, her eldest son Cui Hun died of grief. Bereaved of both her husband and a son, she converted to Buddhism in order to purge her mind of worldly desires. She also gave a good education to her younger son Cui Mian so that he could succeed his father as head of the family. Eventually, Cui Mian was promoted from the Deputy Director of the Archival Bureau (mishu shaojian) to the Left Mentor (an assistant official under/to the prince) with additional honorific title of Chaosan Dafu(literally Grand Master for Closing Ceremonies. The epitaph eulogizes Wang for having educated her sons and grandsons properly and thus enabling them to 'bring glory to their country'. Besides, she brought constant peace and happiness to the family, which was content with their life and thought nothing of their limited means. According to the epitaph, Wang Yuan, at the age of seventy-four, died of illness on the twenty-first day of the fourth lunar month in the ninth year of Kaiyuan period at Chongzheng House in the Eastern Capital. She was given a simple burial on Mangshan Mountain. This epitaph was engraved seventy-two years after her husband's death, when the family rebuilt her tomb.

The epitaph gives a vivid and detailed account of the tomb occupant’s attitude towards life and her distinctive personality by recording her specific words and conduct. Written in plain and clear language, the text reflects the stylistic reform of epitaphs since the Dali period of the Tang Dynasty. The epitaph of Wang Yuan is kept in Henan Museum, together with the epitaph of her husband Cui Kai and that of her grandson Cui Youfu. All the three epitaphs were written in official script by Xu Gong, a famous calligrapher then. His official script preserves the smoothness and rhythm of dots in Han style, but replaces the overtone of seal script with that of regular script; besides, compared with Han official script, the characters are taller and without long downward strokes to the left or right. These features became characteristic of Tang official script (Fig. 3).

Tan Shuqin is an associate researcher at Henan Museum. Since 1986, she has worked at museology and archaeology for twenty-five years. She is mainly devoted to the study of ancient stone carvings, particularly Han stone reliefs, steles and epitaphs, and ancient Buddhist sculptures. In 2008, she acted as editor-in-chief of the volume on steles and epitaphs in the part about cultural relics in Compendium of Central Plains Culture, a national key project.