Tan Shuqin,works at museology and archaeology for twenty-five years, devoted herslf to the study of ancient stone carvings, stone reliefs, steles and epitaphs, and ancient Buddhist sculptures.

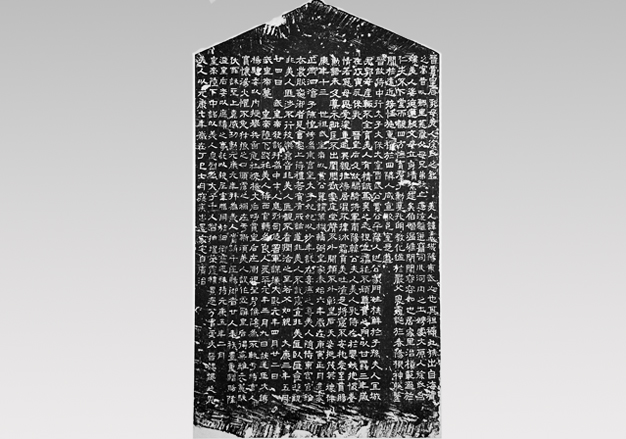

The tombstone was carved out of a piece of caesious limestone with a Gui-shaped head and a square body. Characters of official script are inscribed on both sides of the tombstone (Fig.1). There are 23 lines, each having 33 characters, on the front, and 16 lines, each having 23 characters, on the back. The first line reads “the inscription of Meiren Xu who was the nursing mother of Empress Jia of the Jin Dynasty” and the inscription records in detail the life of the tomb owner Xu Yi, including her name, birthplace, family background, marriage, admission to the imperial palace and conferment of ladyship, and matters concerning her sickness, death and burial, relating to the fight in the court, and the private life of the nobles and imperial family of the Western Jin Dynasty.

Fig.1 The inscription on the tombstone of Xu Yi (back)

According to the inscription, Xu Yi was born to a poor family with no kin. There has been no record of his family name and she adopted the surname of her husband. “Meiren” was the imperial title granted by the emperor and was also a respectful address by the writer of the inscription. “Due to the famine and chaos, her parents and brothers died, and she fled her hometown and came to the territory of Sichuan and Henei and married to a scholar from Taiyuan by the family name of Xu.” She gave birth to and raised many children and managed her home well. She became famous in her neighborhood for her benevolence toward and favor to her fellow townsmen. As Guo Huai who was the wife of Jia Chong, the strongman of the Western Jin Dynasty at the moment, could not raise her children each time after giving birth, Xu Yi was then called to enter the palace in the third year of Ganlu period to nurse the two daughters of Jia and “built the mother-daughter relationship with them.” Later Xu Yi accompanied Jia Nanfeng, the first daughter of Jia Chong, to enter the palace when the latter was selected wife of the crown prince and had since received the treatment of the imperial family. After the death of Emperor Wu on the 22nd of the 4th lunar month in the first year of Daxi period, the crown prince Sima Zhong ascended the throne and Jia Nanfeng became empress. As a result, Xu Yi’s status was elevated gradually from the initial “Zhongcairen” to “Liangren”. In the first year of Yuankang period, Xu Yi received the imperial title of “Meiren” for her protection of Empress Jia in the palace coup. In her late years, Xu Yi returned home as her sickness prevented her from continuing serving the empress. The emperor and the empress designated people to check her physical condition every day, and sent imperial physicians to treat her disease and gave her imperial medicines. Whenever the empress had rare and precious food, she always gave some to Xu. In the eighth year of Yuankang period, Xu died at the age of 78 and was buried in the following year.

The entire article was written in a succinct but beautiful language, vividly presenting the story of a nursing mother who came from an impoverished family in the countryside, was extremely hardworking and was forced to become a servant in the imperial palace but later, with her wisdom, promoted to be a female court official and received the treatment of imperial concubines. The fact that Xu Yi was forced to leave her home and become the nursing mother of the two daughters of Jia Chong reflected the corrupt and extremely extravagant life of the noble families at the time. The special status and living environment not only built up her observant, smart and quick-witted characteristics but also involved her against her wish in the court fight and hence impacted the history. The inscription mentioned historical figures and events involved in the “Upheaval of the Eight Princes” during the Western Jin Dynasty that can be used to cross-check the content in the Book of Jin.

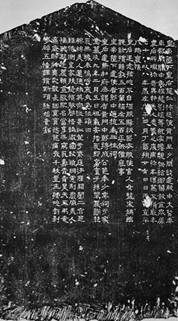

The inscription was written in the rigorous, stately and graceful official script and specifically enhanced the brush strokes in the curves following a horizontal line, stops and changes. (Fig.2) The tombstone inscriptions of the Han and Wei Dynasties unearthed from Luoyang and Yanshi in its east demonstrate similar styles in structure and brush strokes, creating a strong decorative effect. These works lasted for about forty years, reflecting the local calligraphic style that was then popular in Luoyang and Yanshi and was later referred to by experts as “Luoyang Style of the Western Jin Dynasty”. [2]

The fine craftsmanship of the tombstone is reflected in the fact that the calligraphy, Shudan (written in red ink) and carving technique were all completed under the supervision of the government. It was very rare in the feudal Chinese society where female status was normally inferior to that of men to build a stele to praise a nursing mother. It is a real proof of the role and status of the female in the feudal society.

Fig. 2 Detail of the inscription on the tombstone of Xu Yi in the Jin Dynasty

Most tombstones we have seen are in a square shape with a stone and a cover, jointly called “a case”, which, after standardized, became the commonplace burial accessory. The small stele shape of Meiren Xu indicates that the stele appeared earlier than the inscribed tombstone. Both share the same cultural origin.

In as many as thousands of tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty unearthed in Henan Province, tombstone inscriptions have been very rare. The Wei and Jin Dynasties were the transitional period that the inscribed tombstone was standardized. Tomb steles were strictly prohibited by Emperor Wu of the Wei Dynasty and Emperor Wu of the Jin Dynasty. In the fourth year of Xianning period, Emperor Wu of the Jin Dynasty issued an imperial decree that stated: “stone beasts, steles and inscribed tombstones are all forms of a self-praise that only promote hypocrisy, cost fortunes and do no good to people. They will cause damages more than anything else and therefore should be prohibited. Anyone who violates the decree, although pardonable, must be ordered to destroy such structures.” As a result, tombstones that had been very popular since the Eastern Han Dynasty disappeared. This explains why there are just a few tomb steles from the Wei and Western Jin Dynasties unearthed so far. Despite the prohibitive decree, people would erect steles to commemorate the deceased. To avoid open violation of the decree, people created small tombstones in the shape of stele and put them inside the underground chamber. They usually measure less than one meter in height and half a meter in width and are erected inside the tomb (Fig.3). The prohibition on steles in the Wei and Jin Dynasties caused the popularity of a large number of buried tombstones, which marked a transitional period in the history of inscribed tombstone and symbolized the emergence of another form of burial custom.

Fig. 3 Restored display of the inscribed tombstone in Pei Qi’s tomb of the Western Jin Dynasty

(photographed in the Luoyang Ancient Tombs Museum)

The shared cultural characteristics and patterns of changes demonstrated in burial forms in the Jin Dynasty gave rise to an independent system and are referred to as the “Jin System” by the famous archeologist Yu Weichao. [3]

More inscribed tombstones of the Wei and Jin Dynasties have been unearthed in archeological excavations since the Qing Dynasty. They are all small but in a variety of shapes and forms with simple characters. Some of them have shown the format normally seen in the tombstone inscriptions. These small-stele tombstones boast different shapes, including Chi (hydra)-headed, round-headed, Gui-headed and rectangular-bodied or rectangular tombstones, reflecting characteristics in the design in its early stage.

I Gui-headed and rectangular-bodied tombstone

The earliest Gui-shaped tombstone was that of Sun Zhongyin dating back to Xiping period of the Eastern Han Dynasty that was unearthed in Gaomi City, Shandong Province. It measures 88 cm in height and 34 cm in width. Similar examples include the tombstone of Meiren Xu, the inscription on the coffin of Guo Huai, wife of Jia Chong in the first year of Yuankang period (Fig.4), and the tombstone of Xun Yue of the third year of Yuankang period of the Jin Dynasty (Fig.5). The smallest Gui-shaped tombstone of the Jin Dynasty was that of Zhang Yongchang, General Zhennan in the fourth year of Taishi period, which only measures 28 cm in length and 13 cm in width.

Fig. 4 The inscription on the coffin of Guo Huai of the Western Jin Dynasty

Fig. 5 The front of the inscription on the tombstone of Xun Yue of the Western Jin Dynasty

II. Chi-headed and rectangular-bodied tombstone

Among tombstones of the Jin Dynasties, those with a Chi-head and a rectangular body are the closest in shape to a stele, such as the tomb stele of Guan Luo, who was the wife of Xu Jun in the first year of Yongping period in the Western Jin Dynasty (Fig. 6) and that of Zhang Lang in the first year of Yongkang period (Fig.7). The tomb stele of Guan Luo measures 59 cm in height and 25 cm in width. It was unearthed in Luoyang in 1930 and is now in the collection of Xi’an Stele Forest. The tomb stele of Zhang Lang of the first year of Yongkang period in the Western Jin Dynasty (300) measures 53 cm in height and 27 cm in width. It was unearthed in Luoyang in 1916, and was brought to Japan in 1919 but was broken in the severe earthquake that hit Japan in 1924 and destroyed the museum. [4]

Fig. 6 The tomb stele of Guan Luo in the Western Jin Dynasty

Fig.7 The tomb stele of Zhang Lang in the Western Jin Dynasty

III. Rectangular tombstones

Rectangular tombstones are more commonly seen in the Jin Dynasty, such as those of Shi Xian (Fig.8) and Shi Ding (Fig.9) of the second year of Yongjia period of the Western Jin Dynasty unearthed in Luoyang, Henan Province. A special tombstone with inscriptions was unearthed from Babaoshan of Beijing, which belongs to Hua Fang, who was the wife of Wang Jun, Cishi (feudal prefectural governor) of Youzhou in the first year of Yongjia period of the Western Jin Dynasty. It measures 131 cm in length and 57 cm in width with a total of 1630 characters in official script, making it the tombstone of the Jin Dynasty with the most characters unearthed in Beijing, and one of those with more characters of the Jin Dynasty unearthed in China. [5]

Fig. 8 Western Jin Dynasty, the inscribed tombstone of Shi Ding

Fig. 9 Western Jin Dynasty, the inscribed tombstone of Shi Xian

Tombstones with inscriptions of the Western Jin Dynasty have demonstrated a variety of styles. They are an important part in the transition from stele inscriptions to underground tombstone inscriptions. In addition, the calligraphic style of inscriptions on tombstones in the Jin Dynasty was uniquely different from that of other periods. These common cultural characteristics and patterns of changes have provided authentic, reliable and valuable materials for the research of archeological theory of tombs of the Western Jin Dynasty and transition in the ancient Chinese burial system from “Zhou System”, “Han System” to “Jin System”.

“Zhang Chang Drew Eyebrows for His Wife and Han Shou Stole Perfume”

— The story of “Han Shou stealing perfume”

The inscriptions on the tombstone of Meiren Xu mentioned Jia Wu, the younger daughter of Jia Chong and Guo Huai nursed by Xu and Han Shou, Jia Wu’s husband. A widespread story in history tells how the two met and got married.

According to Shishuoxinyu (Tales of the New Era)• Huoni, Han Shou was a handsome man and was hired by Jia Chong as his assistant. After seeing him, Jia Chong’s daughter fell in love with him and missed him very much. Later her maid came to Han Shou’s home and told him all about it and also mentioned how beautiful Jia Chong’s daughter was. Han Shou then asked the maid to arrange the meeting between the two and came to spend the night with Jia Chong’s daughter. The change to his daughter was detected by Jia Chong and he could smell the special perfume on Han Shou. It was sent by a foreign country as tributary and once worn by a person, it would not disappear within months. As Emperor Wu only granted the perfume to Jia Chong and Chen Qian but nobody else, Jia suspected that Han Shou had an affair with her daughter. After finding out what happened from his daughter’s maids, Jia Chong kept it a secret and married his daughter to Han Shou. “Han Shou stealing perfume” was used by later generations to mean that a woman falls in love with a man or imply a private affair between a man and a woman. Liu Xiaowei, a poet from Liang during the Southern Dynasties wrote in his poem that was entitled “Feng He Zhu Liang Poem”: “Zhang Chang drew eyebrows for his wife and Han Shou stole perfume”. The story then became the topic of many poets and was also reflected in novels and dramas in the later periods.

Han Shou, with no biography in the Book of Jin, was mentioned in the chapter of Jia Chong’s Biography in the book. He once served as Sanjichangshi (Cavalier Attendant-in-ordinary) and prefectural magistrate of Henan and died in early years of Yuankang period. The column in Han Shou’s Spirit Way of Yuankang period in the Western Jin Dynasty (291-299) was unearthed before the foundation of the PRC in Luoyang, the remaining part of which measures 113 cm in height and 33 cm in diameter and is now in the collection of Luoyang Museum of Stone Carving Art in Guanlin Temple. (Fig.10)

Fig. 10 The stone column before the tomb of Han Shou of the Western Jin Dynasty

Although very few tombstones with inscriptions of the Western Jin Dynasty have been unearthed, it is coincidence that the tombstone of Guo Huai, the wife of Jia Chong and the mother-in-law of Han Shou was also unearthed in Luoyang. The inscription on the coffin of Guo Huai of the sixth year of Yuankang period in the Western Jin Dynasty (296 A.D.) was found in 1930 in Luoyang. The stone measures 76 cm in height and 31 cm in width (see Fig. 4). The successive discovery of the inscription on the Tombstone of Xu Yi, the stone column before the Tomb of Han Shou and the inscription on the coffin of Guo Huai from the Western Jin Dynasty in Luoyang verify what has been recorded in historical literature. Stories of the three people were associated and mentioned in all the three tombstone inscriptions, sparkling interesting imagination on the distant history.

According to the tombstone inscription, Xu Yi was granted titles of “Zhongcairen”, “Liangren” and finally “Meiren” to honor her contribution in fostering and assisting Empress Jia, indicating that in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, the title of “Meiren” was of a higher rank than that of “Zhongcairen” and “Liangren”. Do you know if “Liangren”, an imperial title granted to female officials in the court, has other meanings in ancient times? Does it have anything to do with “Lang” and “Niang”?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please feel free to send us email, we are waiting for your answers and participation, and your comments, answers and suggestions will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments some time in the future.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net