Who Was Guo Zhong?

Tomb No. M2009, which was discovered in 1991, was the largest among the tombs of the Guo lords that had been excavated to date in the State of Guo burial grounds in Sanmenxia, as well as the one with the finest artifacts and signs pointing to the highest standards. Among the 4,597 artifacts of various types from the tomb, there were more than 200 large bronze ritual objects. Many of the objects had inscriptions with the name Guo Zhong, showing that this was his tomb. The specifications, designs, and the style of the inscriptions indicate that the tomb dates from the late Western Zhou Dynasty.

Guo Zhong was a vassal of King Li of Zhou. His courtesy name was Zhangfu, and his posthumous title was Duke Li. In the 13th year of his reign King Li set off for a campaign against the Huai tribes, who had overrun the Western Zhou heartland. Guo Zhong and other commanders participated in the campaign. In the war, the Zhou king and commanders like Guo Zhong not only fended off their enemies and recaptured property and prisoners that had been seized, but also persuaded more non-Chinese tribes at the southern and eastern frontiers to acknowledge the supremacy of the Zhou Dynasty. As a result, Western Zhou’s revenues increased, and the war also served as a warning to the other feudal lords and tributaries.

But despite his military exploits, Guo Zhong was known to historians as a personal favorite of the Zhou king and the culprit for sparking the People’s Riots during the reign of King Li. While the direct cause of the riots was the vast fortune amassed by Lord Rongyi — which funded not only the luxuries enjoyed by the Zhou slave-owning and aristocratic classes, but also King Li’s campaign against the Huai tribes. So as King Li celebrated his victory over the Huai, the people who had been pushed to the brink rebelled in the first uprising of the common people in the history of China. For this reason, historians consider the ethnic war against the Huai the most important reason behind the People’s Riots. And Zhangfu, the lord of Guo, naturally came to be called a “personal favorite” and the main culprit behind the riots.

Guo Zhong’s unbounded loyalty to the absolute monarch over the people’s needs ended in their revolt and a soiled reputation for himself. One might consider him a tragic figure.

In The Book of Rites: Yuzao, it was written that the king wore white jade and a black ribbon, while aristocrats wore shanxuan jade and a vermilion ribbon. Only the king could have white jade. But Guo Zhong, who was only a feudal lord, also had a piece of white jade with a dragon design. Archaeologists who discovered this white jade disc thought that the Zhou king had probably given it to Guo Zhong. Then what would be the reason for the gift?

Your answer please, if you have any questions or answer, please feel free to send us email, we are waiting for your answers and participation, and your comments, answers and suggestions will be highly appreciated. We will select and publicize the most appropriate answers and comments some time in the future.

Weekly Selection Email: meizhouyipin@chnmus.net

Jade discs have existed through all periods in Chinese history. The persistence of their use, the geographical area over which they have been found, and their sheer number are without peer among all the different kinds of jade objects. Their cultural significance is also profound. Here, we will compare several noteworthy examples from different eras.

This jade disc from the Hongshan Culture (Fig. 1) was excavated from Tomb No. 21 in Stone Mound No. 1 at the Niuheliang site in Liaoning. The disc measures 14.7 cm in diameter and has a translucent green-gray color. It is a slightly flat circle, with the edges resembling a thin knife. Two perforations puncture the top.

This jade disc with ritual carvings (Fig. 2) came from the Liangzhu Culture. It was found in Anxi Township in Yuhang County, Zhejiang and has an outer diameter of 26.2 cm, an inner diameter of 4.2 cm, and a thickness of 1.2 cm. Its gray-green surface is mottled with dark spots. Ritual designs are engraved in shallow intaglio on both sides of the disc. The design on one side is a frame in an inverted T shape with a bird or turtle within; the corresponding area on the other side has a design resembling a rectangular tool, weapon, or half-scepter.

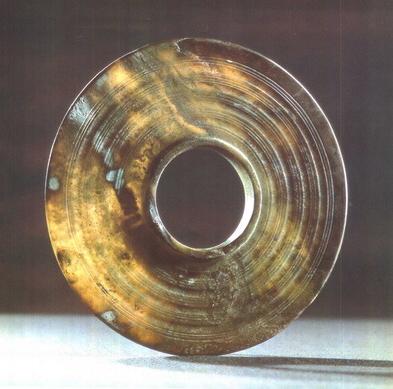

This jade disc from the Shang Dynasty (Fig. 3) was found in the tomb of Fu Hao in Yinxu, Anyang. Its outer diameter is 18.6 cm, and its inner diameter is 6 cm. Brown patches and gray-white grooves dot its green surfaces. Both the edges and the center hole are more rounded, and the surfaces around the hole on both sides are slightly raised. There are four sets of smooth, regular concentric circle designs on both sides, each consisting of one thick line and three finer lines. The lines are tidy and smooth.

This is a jade disc from the early Spring and Autumn Period (Fig. 4.). It was found in the tomb of Huang Junmeng and his wife in Baoxiangsi in Guangshan County, Henan. The disc has an outer diameter of 11.6 cm, an inner diameter of 6 cm, and a thickness of 3 cm. The jade is a blackish yellow color with black immersion marks. Coiled snake designs are engraved on one side of the disc. The other side is smooth.

This jade disc from the mid-Warring States Period (Fig. 5) was found in Tomb No. 1 in the State of Zhongshan tombs in Qiji Village, Pingshan County, Hebei. Its diameter is 14.6 cm. The yellow-brown translucent material is daubed in gray immersion marks. Lines are engraved along both the inner and outer edges, and five rings of hooked cloud patterns are carved onto the surface, but these patterns are kept separate.

This jade disc from the early Western Han Dynasty (Fig. 6) was excavated from the tomb of Zhao Mei, King of Nanyue, in Xianggang, Guangzhou, Guangdong. It has an outer diameter of 26.7 cm, an inner diameter of 9 cm, and a thickness of 0.7 cm. The dark green surface is divided into two sections by three lines. A pattern of silkworms in repose covers the inner section. Four sets of combination dragon-snake designs occupy the outer section: the dominant motif of curled double dragons become, at their tails, snakes with open mouths and raised heads.

Due to the constraints of the rudimentary cutting tools available at the time, jade discs from the New Stone Age tended to be irregularly shaped. For example, the edge of the Hongshan Culture disc is as thin as the blade of a knife, and the Liangzhu Culture disc’s inner edge is thicker than the outer edge. The discs are usually made of light green, green, gray-white, or light yellow jade and have well-polished smooth surfaces.

In the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, jade discs were ritual objects reserved for the use of the aristocracy. The discs are generally smooth, round, and smaller than those from the New Stone Age. The outer and inner edges have similar thicknesses, and the pairs of holes in the center are regularly shaped. The surfaces of the discs are usually smooth without patterns. Light green, green, and white jade from Xinjiang and jade from Nanyang and Xiuyan figure prominently.

In the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, jade discs began to be a common clothing accessory. Ritual jade discs were usually larger than those used as clothing accessories. The surfaces of most jade discs were divided into inner and outer sections, each with its own designs. Popular designs included grain-of-wheat and dragon patterns. New variations appeared, including discs with extensions at the outer edges or from the center hole sculpted into vivid animal forms in openwork. Light green, green, and white jade from Xinjiang figure prominently.

Han jade discs continued in the style of the Warring States Period and brought slight variations. They became larger. More dragons, phoenixes, and birds were carved in openwork, and the protrusions in the grain-of-wheat and woven-mat patterns were larger and farther apart. Combination patterns became more popular, and written expressions of good wishes also entered the design repertoire. In the Eastern Han Dynasty, the discs were thicker, and the surfaces of the outer edges were slightly curved. However, the number of jade discs was reduced.

In the Tang Dynasty, both sides of a disc were usually decorated: one with either grain-of-wheat or woven-mat patterns and the other with the faces of animals, coiled chi dragons, or flora. Thick lines were usually engraved along the contours, with finer engraved lines as trimming. At times, the lines were not solid. During and after the Tang Dynasty, the ritual significance of jade discs gradually diminished and was overtaken by a flavor of daily life.

In the Song Dynasty, jade pieces that imitated the ancient styles became popular. Jade discs from this period had rounded, barely-apparent corners. In contrast with the grain-of-wheat patterns from the Warring States Period, the grains in the Song grain-of-wheat patterns were spaced close together as well as vague, with less momentum in the gyrations. The chi dragons from the era were characterized by long forked tails that coiled inward at their tip.

Most Yuan Dynasty jade discs imitated the Tang style and were small articles used as clothing accessories. They were usually decorated with carvings only on one side. The discs felt bulky, and the grains were sparse and had no pattern in their configuration. The craftsmanship in these discs were unremarkable, with deep incisions and incisions outside the edges of the discs a frequent occurrence. But there were also fine examples of openwork carvings.

More jade discs from the Ming Dynasty have been found than from the prior three dynasties. Light green and white jade were the usual materials, and there were also a small number of discs made of green jade. The discs were generally smaller. Circular chi dragons carved in relief were common, as well as grain-of-wheat and cloud designs. The round, large doornails in the doornail designs often showed signs of the tubular drill bushings. The craftsmanship in Ming Dynasty jade discs tended to be rougher and have a more spontaneous feel.

Qing Dynasty jade discs usually came in the form of small accessories. They were thicker, and the center holes were smaller. Conjoined double discs appeared, as well as geometric designs, designs conveying auspicious futures, and designs featuring human figures. They tended to be more realistic. During the reign of Emperor Qianlong, jade discs in imitation of ancient styles were so well-made that they could be mistaken for discs from ancient times. But in the late Qing Dynasty, the materials used for discs and the craftsmanship were both poor, representing a steep decline in the quality of discs.

In modern times, jadeite, agate, and other types of jade came to be used to make jade discs. There is more variety in jade discs, which have become part of people’s daily lives.

Between the New Stone Age and today, jade discs have reached a point in their journey from being mysterious aristocratic ritual objects to simple, common objects of daily life. Their history mirrors changes in societies and tastes.

The jade disc is a traditional Chinese ritual object. It first appeared between five and six thousand years ago during the late Neolithic Age. The tombs of the Liangzhu Culture from the Taihu Basin contained the most important large collection of funerary jade discs. These jade discs were relatively large, but their shapes tended to be irregular and their craftsmanship rather unrefined. There were usually no carvings on the surfaces. In the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, the use of jade discs was common. Their specifications became more standardized, and there was variety in the decorative carvings. The most popular designs were double-hooked cloud patterns, dragon patterns, and phoenix patterns. In the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, the discs became thinner. Millet and woven-mat designs took the place of the Western Zhou double-hooked, dragon, and phoenix designs carved in intaglio. Discs with openwork designs attached on the edge as well as linked discs also appeared. In the Han Dynasty, the openwork designs at the edges of the disc gradually lengthened. The decorative carvings became more elaborate, giving rise to discs with several layers of carvings and words expressing good wishes. Jade discs were less popular after the Han Dynasty. Those that dated from after that time copied the specifications and designs from prior periods.

Objects similar to jade discs include jade rings (huan) and jade arm bracelets (yuan). It was written in Erya: Explaining Utensils: “If the rim is larger than the hole, it is a disc. If the hole is larger than the rim, it is an arm bracelet. If the rim and the hole are the same, it is a ring.” Based on the archaeological findings, Xia Nai thought that there were no exact multiple relationships between the diameters of the object and the hole in its center. Therefore, when the center hole is larger than half of the object’s diameter, it is considered a ring. When the center hole is smaller than half of the object’s diameter, it is considered a disc. For this reason, most ancient jades familiar to us now are either jade discs or jade rings, but jade arm bracelets are rare.

Jade discs had been widely used. It served as a symbol of power and status, a clothing accessory, a funerary ritual object, a gift, and a token for a pledge. In ancient times, its most important role was as a ritual object in the worship of the heavens, the earth, ancestors, and gods and spirits. It was written in The Rites of Zhou: Offices of Spring: the Great Official of the Imperial Family: “The six jade ritual utensils are used to worship the heavens, the earth, and the four directions: the dark green disc for the heavens, the yellow tube for the earth, the green scepter for the east, the red half-scepter for the south, the white tiger for the west, and the black half-disc for the north.” Jade discs used as ritual objects were usually made of jade of the highest quality and had the finest textures, designs, and craftsmanship. The secondary function of jade discs was as clothing accessories that acted as markers of status. These jade discs were usually smaller and had holes for a string to thread through.The Book of Rites: Yuzao states that “the gentlemen of ancient times always wore jade…the piece of jade was never taken off without reason. For a gentleman, jade was like virtue itself.” This shows that people in ancient times used jade as a symbol of status. In addition, jade discs were also funerary objects that were thought to protect the body. The textures of these jade discs were usually rougher and had no designs. After the Han and Tang Dynasties, the function of jade — including jade discs — as ritual objects gradually weakened and became the art objects and ornaments as they usually are today.

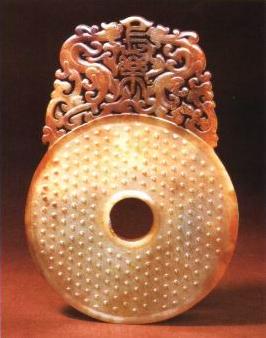

Crafted from high-quality Hetian white jade, this white jade disc had lain on the shroud in the tomb of Guo Zhong. The white disc has a slightly greenish color and glistens with clarity and warmth. It is almost a perfect circle and is otherwise regularly-shaped. Both sides are engraved with modified and stylized dragon patterns, with smooth, flowing lines that reflect superior craftsmanship.

Guo Zhong once reigned over the state of Guo. His tomb yielded 1,050 pieces of jade artifacts, making it another pre-Qin Dynasty tomb with a large collection of high-quality jade artifacts after the discovery of Fu Hao’s tomb in Yinxu, Anyang. This disc is notable not only for its fine texture and regular form, but also for its beautiful and well-crafted engravings. It is an uncommonly handsome specimen of pre-Qin jade handiwork.

A premium type of Hetian jade, white jade has a smooth, hard texture and a glowing translucence. Its creaminess has earned it the name of “mutton-fat white jade.” In The Book of Rites: Yuzao, it was written that “the king wears white jade and a black ribbon, while aristocrats wear shanxuan jade and a vermilion ribbon.” It is apparent that people in ancient times wore jades and ribbons of different colors in accordance with their status. Before the Qin Dynasty, the fact that the king wore white jade showed the existence of a strict hierarchy. Although Guo Zhong was only a feudal lord of the state of Guo under the Zhou Dynasty, he possessed a white jade disc with dragon patterns. According to the archaeologists who found the disc, this jade disc was probably made by the jade workshop of the Zhou king’s court and might have been a gift from the Zhou king to Guo Zhong.